Part 1 of 3: Is Bilderberg More Important Than The G7?

According to some observers, last year’s Bilderberg Meeting, held over 11-14 June, 2015 at the Interalpen Hotel, near the town of Telfs-Buchen in Austria, was a more significant event than the Group of Seven meeting that had just preceded it across the border in Germany. Bilderberg is “every bit as important as the G7”, claimed The Guardian’s (Jun. 08, 2015) lone correspondent, Charlie Skelton; if not a “much more decisive meeting place [ein viel entscheidenderes Treffen statt]”, wrote Thorsten Schmitt from Extrem News (May 30, 2015). Yet some of the Bilderberg meeting participants – the few that deigned to even speak or write about it – insisted that the 2015 gathering was a very interesting but ultimately benign occasion. Michael O’Leary, CEO of Irish airline Ryanair and newly appointed Bilderberg Steering Committee member, for example, after mocking claims it was a “big conspiracy” told Irish radio that his first Bilderberg meeting had been a “terrific experience” and “very educational.” Another first time participant, Trine Eilertsen, Political Editor of the Norwegian newspaper Aftenposten wrote that the “discussions and introductions” at Bilderberg were “very useful because participants spoke so freely.” But she also dismissed as “distant from reality”, a columnist writing in a rival publication, Aftenbladet (Jun. 13, 2015) who criticised her participation and considered it “naïve” of Eilertsen not to see anything sinister in a secret meeting of billionaires, politicians and journalists.

Such sharply conflicting assessments naturally raise the question as to what actually transpired at the 2015 event, behind closed doors at the sumptuous five-star Interalpen Hotel. Was the Telfs-Buchen meeting really on par with or even more important than the G7? If so, then why did O’Leary and Eilertsen not see it that way? What did they talk about? What was its political impact? Did mainstream media coverage of the event improve over the previous year? And how did the representatives from the alternative media fair in their attempts to penetrate Bilderberg secrecy and security? In this three part article we will try to answer these questions, and more, to try to shed some more light on the 2015 Bilderberg meeting.

Is Bilderberg Bigger than the G7?: A Question of Security

With barely a week separating the two events, as well as being held in venues just 27km apart from each other, comparisons between the 2015 G7 Summit and Bilderberg Meeting were inevitable. The principal argument made by Bilderberg’s critics was that the timing of the two meetings was in itself an indicator of G7’s subordinate status, even though in 2015 the order was apparently reversed with the Bilderberg meeting following that of G7. Paul Joseph Watson at Infowars speculated on what this meant:

it’s unusual that Bilderberg is taking place after the G7 conference. It’s normally the other way around. This suggests that Bilderberg’s role in not only setting the consensus, but making the final call on many of these issues will be pivotal this year.

Watson’s argument is interesting, but he provides no evidence that the timing of the G7 summits has ever been driven by Bilderberg. Moreover, Watson’s description of the timing of 2015’s meetings as “unusual”, while certainly true over the long-term—ever since the G7 meetings started in 1975, only four have preceded Bilderberg and in 1998 the meetings overlapped—omits mentioning that three of the last five Bilderberg meetings (2011, 2012 & 2015) came after the G7. So the significance of the timing and order of the two meetings is unclear, other than the preference of both Bilderberg and G7 meeting organisers to hold their meetings during late Spring and mid-Summer in the Northern Hemisphere.

But for most anti-Bilderberg activists the only real evidence that Bilderberg was more significant than the G7 was the different reception the media received from the security forces protecting the two events. Jeff Berwick from The Dollar Vigilante(TDV) website, for example, noted how the Austrian police had turned from being “very nice and helpful to journalists/writers” during the G7 to treating journalists “like potential threats” for Bilderberg. To Berwick this suggested that Bilderberg was “much more important” than the G7. Watson also cited the “intense security” around the Interalpen Hotel as evidence of “how paranoid Bilderberg are about keeping the details of their agenda under wraps”

Given the reports on the heavy-handedness of the smaller Austrian security force left to protect Bilderberg after the G7 was concluded, such a view is to be expected. Austria not only deployed 2,100 police officers in the area for the two conferences—with 1,700 in the main phase backed by 1,100 Army personnel—but also enforced a 31-kilometer exclusion zone around the Interalpen, deployed helicopters armed with machine guns, and had their elite COBRA anti-terrorist force on standby. Even some armoured vehicles were observed. Alternative media blogs and twitter feeds were awash with accounts of being stopped and subjected to humiliating searches at police road blocks, and being harassed in other ways to prevent them, as well as locals and tourists, from getting anywhere near the Interalpen Hotel. The Guardian’s Skelton was to subject to three police identity checks within a half-hour, the final one ending in his hotel room (Guardian, Jun. 11, 2015). This treatment was in marked contrast to the G7 Summit a week earlier where accredited journalists enjoyed a well-appointed press centre (complete with catering, workstations, editing booths and a wireless LAN) and friendly treatment from the authorities guarding the perimeter.

But the excesses of the Austrian authorities were hardly proof that Bilderberg was more important than the G7. The G7 security operation was actually much larger than Bilderberg: there were 17,000 German security personnel deployed to protect the G7 compared to just 2,100 Austrian police for Bilderberg. To protect the G7, the German authorities established an exclusion or “safety zone” around the Schloss-Elmau resort in the Bavarian town of Garmisch-Partenckirchen in anticipation of protests from various radical groups. This reportedly included a “7-km long steel barricade” encircling the castle at Schloss-Elmau, “equipped with cameras, movement censors and every kind of digital security technology”, and 16-km wire fence “to keep protestors at bay.” The German authorities also reportedly removed flower pots and woodpiles, to prevent protestors from using them as missiles. Outside the safety zone German police set up security checkpoints to conduct vehicle searches and identification checks on suspected activists.

But there were other factors at play that explain why the security measures at Telfs-Buchen were so severe. It is worth noting that some of those complaining about police harassment at Telfs-Buchen, also claimed the police had not been so oppressive at the previous two Bilderberg meetings. Skelton, for example, recalled how:

[A]t the Watford conference in 2013, we had a relationship with the Hertfordshire constabulary that was every bit as open and tolerant as Will Smith’s marriage. In fact, our presence wasn’t just tolerated, it was actively supported. They had a team of liaison officers. They even gave us portable toilets, for goodness sake. The same in Copenhagen last year: the cops allowed us right up to the edge of the hotel. They made a genuine (if not always successful) effort to communicate with us, and meet our needs (Guardian, Jun. 10, 2015).

In his final wrap-up Mark Anderson from the American Free Press (published by the Liberty Lobby) tried to paint the security measures as yet another example of the “Bilderberg Syndrome” (AFP, Jun. 22 & 29, 2015, p.3). Yet in his dispatches Anderson repeatedly remarked on how the Interalpen was “the most difficult place this writer has encountered in terms of accessing the hotel or visually confirming its attendees” (AFP, Jun. 11, 2015). In another report he suggested it was the most impregnable Bilderberg meeting location ever:

Furthermore, the Hotel Interalpen, where this year’s conference is happening, is not only apparently the most remote and most difficult-to-access of all the places Bilderberg has met in its 61 years—there also are reports of alternative reporters being harassed by Austrian police (AFP, Jun. 12, 2015; emphasis added).

This suggests the problem may have originated in the overzealousness of the Austrian authorities rather than with the paranoia of the Bilderberg Steering Committee. This, in turn, seems to have been driven by the dire security threat assessments for the G7, such as a US State Department warning of the “high terror threat” from Al Qaeda and Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS). The German and Austrian authorities were also rather worried about anti-capitalist activists and anarchists. In the lead-up to the meetings, Günther Platter, the Governor of Tirol Province claimed there was a danger that violent protestors who had come for G7 would cross the German-Austrian border to disrupt Bilderberg The Bavarian Interior Minister, Joachim Hermann also expressed concern about “violent hooligans” from each country crossing the border to oppose both meetings.

But the core reason for the outrage of Berwick, Skelton, and other alternative media representatives over their treatment outside the Interalpen was the simple fact that Bilderberg was closed to journalists. Without the benefits of the media accreditation they had at Schloss-Elmau, they finally noticed the security measures they had been exempt from at the G7. And given the warnings about Islamic terrorists and fears of violence from anti-capitalist activists, and the presence of the Austrian President, two European prime ministers and numerous government ministers and senior officials at Telfs-Buchen, it was unlikely the Austrians would risk relaxing those measures for Bilderberg. It is also worth remembering that, unless they are invited as participants, journalists performing their craft have always been excluded from Bilderberg. What this means is the claims that journalists were more aggressively kept out in 2015 was because Bilderberg is somehow more important than the G7 is a non-starter.

Is Bilderberg Bigger than the G7?: A Question of Power

Putting aside the issue of security, the other more important question remains: is the secretive Bilderberg conference actually more politically important than the G7? None of the activists and self-styled reporters making this claim bothered to put this contention to the test. Instead for most of these journalists, Bilderberg’s greater power than the G7 was regarded as a self-evident truth confirmed by the excessive security. But a closer look suggests this simplistic portrayal fails to address the substantive differences between the two conferences, and in particular, their respective political power, or what they aim to achieve.

For one, there is a substantial gulf in terms of the levels of official representation at the two conferences, specifically from the G7 countries. At the Group of Seven Summit, held at Schloss Elmau in Southern Germany on 7-8 June, the countries of Germany, France, Japan, United Kingdom, Italy, Canada, and the US, were all (of course) represented by their respective heads of government. The European Union also participated, represented by the President of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker and the President of the European Council, Donald Tusk. In total the eight delegations were headed by one chancellor, four prime ministers, and four presidents. Their delegations included senior officials; in Obama’s case, for example, he was supported by his National Security Adviser, Susan Rice, and other members of the National Security Council staff, his Press Secretary Josh Earnest, and he was also accompanied by four members of Congress.

At Bilderberg, in contrast, the actual level of government representation was somewhat lower than at the G7 Summit, even though far more politicians were at the table. There was one current head of state, Austria’s Federal President, Heinz Fischer, and one former head of state, Princess Beatrix of the Netherlands. And two prime ministers: Charles Michel of Belgium, and Mark Rutte of the Netherlands. In addition there were seven elected ministers or ministerial equivalents; five members of parliament; and nine appointed senior officials. The latter group included: the heads of the Danish and French intelligence agencies; the NATO Secretary General; the Director-General of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons; the UN Special Representative of the Secretary General on International Migration; the US Special Presidential Envoy for the Global Coalition to Counter ISIL; and the Special Adviser on Financial and Economic Affairs to the French President.

Though impressive at first glance, this listing hides the fact the most senior politicalrepresentatives from the G7 countries at Bilderberg were the German Minister for Defence Ursula von der Leyen and the UK’s Chancellor of the Exchequer, George Osborne. As for the five other G7 members: France was represented by a presidential special adviser Laurence Boone; the US, after two years of no official participation, sent just one: Special Presidential Envoy General John Allen; there were no officials or politicians from Canada or Italy; and Japan was not invited. Nevertheless, out of the 127 participants, 75 came from the six G7 countries that were represented at Bilderberg (See Figure 1), but most were not officials.

Figure 1: Nationality of Bilderberg Participants – 2015

Source: Justin Parkinson, “Just Who Exactly is Going to the Bilderberg Meeting?”,BBC News Magazine, June 10, 2015.

The presence of heads of state, prime ministers, ministers and other senior officials at Bilderberg is important, but the absence of key players from the G7 countries suggests that its ability to somehow overrule or direct these official processes may be limited. It is worth noting that at last year’s Bilderberg conference official G7 representation was not much better with only Germany, Canada, Britain and France sending one or more ministers. This sporadic attendance would seem to suggest that as an alternative summit to the G7, Bilderberg someway falls short, but this would be to misunderstand its role.

Both conferences present themselves as essentially informal gatherings, where no formal commitments are made. As the description on the G7 website, put up by the German Government, maintains:

The G7 is an important format for political and economic cooperation among the leading industrial nations. It is an informal group, with no statutes, no administrative structures of its own and no formal resolutions.

The Bilderberg Group also presents itself as an annual meeting where off-the-record discussions can take place, but without any policy commitments:

The conference is a forum for informal discussions about megatrends and major issues facing the world… There is no detailed agenda, no resolutions are proposed, no votes are taken, and no policy statements are issued.

But when it comes to the political power of these meetings, only the G7 appears to hold out the possibility that its deliberations will in time shape policy:

At its annual summit meeting the G7 nations agree on common positions regarding global political matters – in particular in the fields of the global economy, foreign and security policy, development and the climate.

Bilderberg, though, pointedly rejects the notion it has an influence at the political level:

The conference has one main goal: to foster discussion and dialogue. There is no desired outcome, there is no closing statement, there are no resolutions proposed or votes taken.

Whether these contrasting approaches actually work as advertised is another matter. The effectiveness of the G7 had long been contested. Stewart M. Patrick, Director of the Council on Foreign Relations’ International Institutions and Global Governance Program, insists that the G7 plays “an unparalleled role as a global agenda-setter, convener, standard-bearer, and champion of the rules and norms underpinning world order.” But other commentators have questioned the G7’s relevance for failing to “offer a united front on Syria, the most dangerous conflict of recent years”; dismissing it as an “anachronism” for not including China; or having a “false sense of power”; or as representative of a “dying order” that should be supplanted by a “new world order” based on a Sino-American hegemony or “G2”. The G7’s effectiveness can also be measured against the goals set it in its annual declarations; although, like those of its “fundamentally worthless” cousin the Group of Twenty, the G7 Declarations seem to be “vapid” documents that either reflect policies already in place, or provide vague, aspirational commitments that most signatories casually ignore.

While it is certainly true that Bilderberg, despite its larger and exalted roster of participants, is not the G7, and was never intended to function as the G7 summit meetings generally do, as photo opportunities, typically anaemic debates (because most of the important issues have already been resolved at the working-level by ministers and senior bureaucrats), and the issuing of profound but often meaningless declarations; it would be the height of naivety to assume it does not play an important role in shaping policy. Bilderberg’s purpose, as its co-founder Joseph Retinger once explained in a confidential paper to his fellow Bilderbergers, was not to be a “policy-making body” but to focus on the “smoothing over of difficulties and tendencies among countries and the finding of a common approach in the various fields…” (Retinger, The Bilderberg Group, August 1956, p.5). In short, one of its key roles – alongside developing a transnational elite network and facilitating informal diplomacy – is to develop a consensus with the people identified by Bilderberg as representing “the general opinion of the leaders of their country” (ibid, p.7).

The Society of the Elect

But this process of developing a “common approach” has never been a passive affair; certainly not from the point of view of its Steering Committee members. Being at its core a shaping and influencing operation, the Bilderberg Group has always sought out people they believed to be in a position to decisively influence public debates and/or had the ear of those in power; or even the leaders of tomorrow. As Retinger explained, Bilderberg sought out:

men of real international standing, or whose position in their own countries is such as to give them considerable influence in at least an important section of the population, men who in their own field hold a position of authority and enjoy the confidence of their fellow-men… (ibid, p.6; emphasis added).

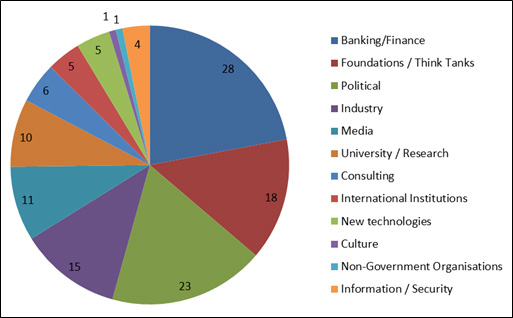

This modus operandi was again quite evident at the 2015 meeting where the ranks of the invitees included all segments of what David Rothkopf once described as the “Superclass”, those few people able to “regularly influence the lives of millions of people in multiple countries worldwide” (Superclass, p.xiv). As with previous year’s meetings, the participants in 2015 comprised: the owners, CEOs and other senior manager of major banks, and corporations, media magnates; political leaders; senior officials from national governments and international organisations; but also a selection for former officials, turned think-tank presidents, consultants, or board members; leading academics; and journalists. The following break-down of participants (Figure 2), drawing on a chart compiled by Paris-Match (Jun. 13, 2015), shows how each sector is represented:

Figure 2: Distribution of Bilderberg Participants by Sector – 2015

Source: David Ramasseul, “The World According to Bilderberg”, Paris-Match, June 13, 2015.

Looking closely at the participant list and it is not hard to find amongst these sectors people of influence; individuals whose great wealth, or lengthy resumes and widespread business and political connections, put them in a position to influence policy-makers and public debates. Despite its tendency to mock the Bilderberg Group, the mainstream media freely acknowledges that many of Bilderberg’s leading figures are powerful in their own right. In the case of Google Executive Chairman and new Bilderberg Steering Committee member Eric Schmidt, for example, much has been made of his strong support for President Obama and Google’s close ties tothe White House. Another Steering Committee member, James A. Johnson from Johnson Capital Partners, also close to Obama, was once described by the Minneapolis Post (Jun. 03, 2008) as “the consummate insider” who was “very rich, very connected and very much behind the scenes”; and by The Atlantic (Jun. 19, 2007) as exemplifying Washington DC’s “political-corporate-cultural elite.” Likewise, Steering Committee member Heather Reisman, CEO of Indigo Books & Music Inc., ranked 24th and 22nd in Toronto Life’s 2013 and 2014 rankings of the 50 most influential people in Toronto; and 33rd in Macleans Magazine’s 2014 list of Canada’s “50 most powerful people.”

First-time participant, Ana Botin, is also a person of note as Chair of the Madrid-based Banco Santander (Santander Group), the 19th largest bank in the world in terms of its assets, estimated at $US1.5 trillion (WSJ, Jun. 10, 2015). Taking over leadership of Santander after her father’s death in 2014, Botin ranked 18th in Fortune’s 2015 list of the 100 most powerful women, who described her as “one of the most powerful executives in the banking world.” Bloomberg dubbed her “the most influential female banker in the world.” Similarly, Bilderberg Steering Committee member Mustafa Koç, Chairman of the Turkish conglomerate Koç Holdings, which he estimated in 2014 to comprise 10 percent of the Turkish economy (Hürriyet Daily News, Mar. 03, 2014), is not insignificant. In 2013 Koç ranked first in the list prepared by a Turkish business publication of Turkey’s “most influential business and economy figures” (Hürriyet Daily News, Sep. 17, 2013).

Perhaps the most revered and reviled of these persons of “real international standing” present at Telfs-Buchen was former US Secretary of State, 92-year old Henry Kissinger. Despite his advanced age, Kissinger remains a highly influential figure both in Washington DC and on the world stage. According to a recent profile in Politico (Feb. 04, 2015), Kissinger has become a “Yoda-like figure, bestowing credibility and a statesman’s aura to politicians of both parties…” Obama’s first Secretary of State, Hillary Rodham Clinton, described Kissinger as a “friend” and admitted having “relied on his counsel” while in office (Washington Post, Sep. 4, 2014). Her successor, John Kerry, also reportedly met privately with Kissinger in 2013 to discuss Russia (Bloomberg, Sep. 12, 2013). But there are some limits to the elderly sage’s access: according to Harvard historian and authorised Kissinger biographer, Niall Ferguson, “Barack Obama is unusual. He is the first U.S. president since Dwight Eisenhower not to seek Kissinger’s advice” (Foreign Affairs, Sep/Oct 2015). Kissinger has met with Obama in the White House in 2009 and 2010 as part of larger delegations; but there is no record of any tête-à-têtes between the two. Nevertheless, Kissinger has advised Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese Premier Xi Jinping.

Clearly, these Bilderbergers are not trivial people.

But even within this gathering there is a hierarchy. When in 1990 UK Liberal Democrat Party leader Paddy Ashdown went to that year’s Bilderberg meeting in La Toja, Spain, he noted in his diary that Bilderberg had been described to him as: “‘fifty people who run the world and twenty hangers on’. No doubt which category I am in!” (The Ashdown Diaries, 1988-1997, p.42). The existence of a distinctive Bilderberg hierarchy has been observed and commented on by some academic analysts. Björn Wendt, for example, a Professor of Sociology at the University of Münster in Germany and author of the book Die Bilderberg-Gruppe (2015), described this structure in an interview last year:

This inner core of the institution (Steering Committee and Advisory Group), I call [the] Bilderberg Group. Approximately 200 people were previously part of this select group. These members of the Bilderberg Group are therefore indistinguishable from those people who are sometimes invited only once to a conference. So you could say: There is an inner circle (the Bilderberg Group) and an outer circle (the conference participants). Even the self-portraits of the Bilderberg Group therefore refute the allegation that there is no organizational structure or membership (Telepolis Jun. 09, 2015; emphasis added).

A breakdown of 2015’s participants (Figure 3) according to their Steering Committee membership and whether they are a regular or first-time participant confirms the existence of such a hierarchy. Nearly half are first-time participants; but just over a quarter are current and former Steering Committee members, with the remainder comprising regular participants:

Figure 3: Breakdown of Bilderberg Meeting Participants – 2015

It is the Steering Committee, which meets at various times throughout the year, which decides the agenda and whom to invite as speakers and participants. It has the ultimate say over the goals and objectives of each meeting, in particular what views it wishes to promote or to challenge. It provides the leadership for the Bilderberg Group and ultimately has responsibility for determining what the political goals are for each meeting. The first-time participants are brought mainly to either present or participate in debates on specialised topics; but ultimately to ensure whatever messages emanate from those discussions can percolate into both the public sphere and realm of the policy-makers.

The Reach of Retinger’s Illuminati

Of course, Bilderberg’s public position is that its conferences are inherently benign affairs, a chance to learn, in some ways akin to an exercise in consciousness-raising for the elite. “I don’t think you’ll get much consensus at Bilderberg”, former British Prime Minister and Bilderberg Chairman Lord Home declared at a rare post-meeting press conference in 1978 at Princeton, “It doesn’t aim to do that. We’re just here to hear these people who know what they’re talking about” (The Odessa American, Apr. 24, 1978). This was the same comforting message conveyed by Bilderberg’s spokesman – who declined to be named – to the Washington Times(Jun. 11, 2015) ahead of the Telfs-Buchen meeting:

“There is no desired outcome, no minutes are taken, and no report is written,” he said. “Furthermore, no resolutions are proposed, no votes are taken, and no policy statements are issued. The conference serves one main goal: to foster discussions on predefined topics. Bilderberg is about gaining insights, fostering understanding and facilitating exchanges of views about the major issues facing the world. With this in mind, the main aim is to broaden the participants’ range of viewpoints, to gain insights and exchange views.”

But the Bilderberg Group’s modus operandi is more carefully calibrated than these soothing words imply: the evidence suggests that speakers and participants alike are selected by the Steering Committee to ensure certain views take centre-stage, and the right people are being engaged and exposed to these ideas to facilitate the dissemination into both the media and government decision-making process the resulting consensus or “common approach” – but without attribution to Bilderberg. This crucial objective of propagating Bilderberg’s deliberations, anonymously, was once spelled out in the confidential minutes for the second Bilderberg meeting, held in Barbizon, France in 1955:

Participants in the Bilderberg and Barbizon Conferences would use, as much as possible, the various meetings and conferences which they attend in order to put forward ideas and suggestions made at Bilderberg and Barbizon. It was hoped that particular use would be made of the press by all concerned for this purpose(Bilderberg Meetings, Barbizon Conference, March 18th-20th, 1955, p.56; emphasis added).

That this policy remains in place was conceded in 2010 by former NATO Secretary-General Willy Claes, who told a Belgian radio station that Bilderberg participants are expected to use the “synthesis” prepared by the rapporteur “in the environments in which they have influence [in de milieus waarin ze invloed hebben]”. And following the 2015 meeting, Aftenposten’s Political Editor Trine Eilertsen was quite upfront about her intention to “use the information that emerged during the meeting, without directly acknowledging where I got it from [bruke informasjon som kom frem under møtet, uten at det direkte fremkommer hvor jeg har det fra]” (Aftenposten, Jun. 16, 2015).

Keeping the proceedings of each Bilderberg meeting under a tight veil of secrecy, specifically who said what and the specifics of the agenda, is thus central to making this process work. This is partially to encourage participants to be candid during the discussions, but it is also intended to conceal from the public the shaping and influencing that drives each session. It hides from the public both the process through which a “common approach” is reached and that Bilderberg is the origin of the consensus or the insights that come into the public sphere. Nevertheless, despite their deliberate silence and shunning of media coverage, there is good evidence, for instance, that the Bilderbergers played a central, though unacknowledged, role in shaping US elite and public opinion towards having a more favourable view of Communist China, setting the scene for President Nixon’s moves to restore relations with Beijing. This was done directly through the Bilderberg meetings, where the existing US policy was challenged by the Europeans; and indirectly, with prominent Bilderberg Steering Committee members driving public debates in the US towards a new relationship with Beijing.

This secrecy also means the political power of Bilderberg is more difficult to assess as most of its deliberations remain confidential; it provides few details of its agenda and has not issued a summary since 1954. In contrast, the G7’s progress in meeting its objectives are easier to track due to its practice of issuing detailed communiques and declarations. Bilderberg may well have a more significant impact than the G7 on transatlantic policies; in some respects it may turn out to be more important, but it is not something the Bilderberg Steering Committee will ever admit to (even though some of its members sometimes speak out of turn). However, as we shall see in Part 2, it is possible to penetrate the veil of secrecy and obtain some insights into how the 2015 Bilderberg meeting has sought to shape elite and public opinion, and come a little further in attempting to answer the question of whether Bilderberg is more important if not more effective than the Group of Seven.

[To be continued in Part 2]